Level 3: Diablo II, Lessons for Game Economy Design, and the Importance of Nomenclature

Player Classification, Evaluating Game Economies, Stones of Jordan, Play-and-Earn, and the importance of names

Stay a while and listen.

There’s many lessons from Diablo II for any game economy designer.

Diablo II is an action, hack-and-slash, dungeon-crawling, RPG, which remains popular today. It lives on in Path of Diablo1 (a Diablo II private server), and Diablo III. Also, Blizzard will launch Diablo II: Resurrected next month, which looks amazing. LFG.

Today, we’ll talk about why Diablo II works for certain players, then move into a study of its in-game economy, introducing tools for game analysis and lessons for game designers along the way.

We’ll use Diablo II as a point of study re: in-game economies, and introduce some new concepts to level up our understanding of game-economy design.

If you know all this, feel free to skip along to the sections where I talk about Play to Earn, Play and Earn and the importance of names.

Classifying Players

Bartle Taxonomy of Player Types

Players can be (loosely) grouped by their playstyles. Why do this? Well, you can think about what type of players you’d like to attract, and market your features accordingly. You can also design gameplay experiences that appeal to them.

Clubs (Killers) - 1%, motivated by chaos

Diamonds (Achievers) - 10%, motivated by mastery

Hearts (Socializers) - 80%, motivated by connection

Spades (Explorers) - 10%, motivated by discovery

Clubs (Killers)

Clubs enjoy… clubbing. Like, bringing a club over your head. Repeatedly. They will kill your avatar, then taunt you. Repeatedly.

Diamonds (Achievers)

Games that can be beaten, and games that allow for completion appeal to Diamonds. These achievements can be set out by the game, or they can be crafted by players themselves. DoubleAgent spent 8000 hours on the Pandaren tutorial island reaching level 110 by picking flowers in WoW: their own personal achievement. If there’s a leaderboard, even if player generated, you know they’ll strive to be the top.

Hearts (Socializers)

Hearts enjoy connecting. Games that provide opportunities to meet and interact with other players appeal to Hearts. They hold fond memories of their experiences in-game with other players. Games are a reason for them to socialize online, not vice-versa. They like wearing cool outfits, chatting, and hanging out. Note that this can happen outside the game.

Spades (Explorers)

Spades enjoy digging. They enjoy making incremental progress in-game, discovering new features and new experiences. Give them opportunities to seek out new surprises, and share them with the rest of the community.

Diablo 2: Lord of Destruction

The core gameplay loop

You choose a character class,

kill monsters for loot and experience,

then kill stronger monsters, for more loot and experience.

Why it’s appealing to players, generally

"Happiness is the feeling that power increases - that resistance is being overcome".2

How Diablo II appeals to individual archetypes

Diamonds love Diablo II because there’s a story, and a definite end to that story. They can also set out their own goals for loot, and for building the perfect character.3

Hearts love Diablo II too. You’re encouraged by the game to team up and play as groups. Diablo II allowed for you to add friends to your list, and blast messages to them. (Battle.net) Players rushed each other, and gave each other starter items. Diablo II, at heart, was really social for its time.

Okay, maybe not just the loading screen. The Clubs were pretty anti-social too.

A player kills another player. More ears for the collection. Hardcore mode.

In-Flows and Out-Flows in In-Game Economies

This is the key piece to understand for play-and-earn games, and is crucial to their success or failure.

Game Economies must manage their currency in-flows (how money enters circulation in the game), and currency out-flows (how money exits circulation in the game).

We’ll expand on this definition in future articles, as well as zoom into sources of inflow and outflow for crypto-games. This is a theme we’ll continually return to: game economies.

First, I must impress on you that a game economy is far more complex than monitoring just the designated in-game currency. In fact, an in-game currency often isn’t enough, as we’ll soon learn from the true history of Diablo II.

Gold, Rings and Runes

In Diablo II, for our players to achieve their goals, they have to become stronger.

How do they become stronger?

They can level up, or get more items.

They could kill monsters by themselves and farm for items, but that takes forever, and they might not even get the correct items for their class. A Sorceress can’t do much with a pair of Claws, and an Assassin doesn’t have much use for a Staff.

They could get items from other players.

But how does one trade?

They either trade directly, or using a currency.

Diablo II has changed currencies three times in its history, and the currencies even change in value as the ladder (the season) goes on.

Gold

Diablo II had an in-game currency called gold, which the designers presumably intended to be the medium of exchange in-game. Here’s how gold enters and leaves the game.

In-Flows

Killing monsters

Selling items to in-game shopkeepers

Out-Flows

Repairing your items

Buying items from in-game shopkeepers

Gambling (gold sink)

Dying (you lose 20% of your gold, and drop the rest on the floor. How embarrassing.)

Gold ended up not being used as a medium of exchange. It was “virtually worthless” when trading with other players.4 Why? It was everywhere, had a max limit (you cannot hold more than a certain amount of gold), and was way too easy to get. None of the best items could be found by using gold either.

Items in the last act often sold for 35,000 gold, and the maximum expense one often had was a few thousand dollars. In addition, players could stack a stat called “gold-find” (up to 600%) to vastly increase the amount of gold dropped.

So transacting items became difficult. The users would have to barter for the items they’d like.

Eventually, the player base needed to decide on a currency.

They needed an item to serve as the standard of value to compare different desirable items. The item needed to be small enough to be carried around, but it also needed to be valuable enough so that you wouldn’t have to carry so many around.

Stone of Jordan (SoJ)

Players started using The Stone of Jordan as currency. It was a ring, that could be equipped.

Why? It wasn’t too common, but common enough to be used as a medium of exchange, and it fulfilled all the criteria above.

In-Flows

Killing monsters

Out-Flows

Players wearing them for their stats

(Eventually) Selling to merchants for the Uber Diablo event

Well, it worked well enough — until players discovered an exploit. Some say they were duplicated en-masse, such that they became effectively worthless.

Because of the massive over-supply, anyone holding value denominated in SoJs were instantly debased, and SoJs were no longer used to trade items.

What does this teach us? Currency can fall in and out of favor over history.

High Runes (HRs)

High Runes are the some of the rarest items in Diablo II. There are eleven of them, ascending in rarity: Mal, Ist… up to Zod.

It was not uncommon to see such trades listed: “faith lv14 fana gmb for 2hr”.5

Basically, high runes acted as currency after Stones of Jordan failed. They were fungible to a degree, and were incredibly rare. They were the “100 dollar bills” of the game.6

In-Flows:

Very rarely drops from mobs. (Jah has a 0.0002% drop rate from Mephisto on Hell difficulty.)

… that’s the only way this currency enters the game legally.

Out-Flows:

They can be used to create rune-words, some of the most powerful items in game.

They can be composed into higher runes.

I really liked this quote from diablo-archive, which captures how the value of high runes change over time.

“As a ladder season progresses and the economy stabilizes, the value of HRs drop substantially due to inflation, eventually reaching a point where each high rune shares a common value. This makes it much easier to acquire expensive runes you may need to create high valued Rune Words.”

So they have a deflationary element as well, because of their utility in making rune words! Because high runes have utility, and people wanna use them, they take them out of circulation. Like real-life gold being used for jewelry.

This is balanced against the amount of players ‘magic-finding’, or repetitively killing monsters in-game to get loot.

Why study this?

Well it’s cool! But beyond coolness, it has lessons for real-life economy design: both in meatspace and metaspace.

Try not to debase the currency you intend to have as a medium of exchange, whether by accident or on purpose.

We have to be very careful about the security of our monetary system, it might cost us money!

Currencies are not used just because we want them to, or designed them to. They are used because they make sense for the player.

We have a lot to learn from Diablo II.

What could Diablo II have done to stabilize gold as a currency, for example?

No hard limit. (Don’t make it difficult to carry.)

Create gold sinks — ways to spend your gold. (they tried with “gambling”, the OG loot box — but gambling was too dissatisfying)

Prevent speeding up gold farming from monsters (nerf gold-find)

Have, and enforce, a far stricter botting and hacking policy

Some are more easily implemented than others.

Names & Great Expectations (Play-To-Earn and Play-and-Earn)

Play-to-earn game economy designers have a great challenge ahead of them.

When their economy, they have the weight of livelihoods upon their shoulders. They’ll have angry players who bought game assets as “an investment” complaining about the “price dumping”7.

You may not have promised that, but its become that in their minds, primarily because of the messaging around a game.

On Names: Play to Earn & Play and Earn

The type of player you attract to your game matters significantly for your monetization. How do you brand the game?

What are the implicit and explicit values you expose to your player-base, either with features or your marketing materials?

Different players will spend differently, and they’ll also bring different intentions to the game.

I tweet below on why that’s the case.

If you got through that tweet thread, let’s talk about the importance of names.

During my Grand Strategy course in New Haven, we discussed global challenges related to the environment.8

The question: how does one convey a sense of urgency around those challenges?

Global warming is tepid. Warming is mild. We’re not around a small fire here, we’re not warming up toaster strudels, delicious though they may be.

Climate change is even more ambiguous. Change for the better or worse? Changing how? Climate delta conveys the same, but is even less impactful.

The professor suggested climate destruction.

A (revised) Taxonomy of Play-and-Earn Gamers

For play-and-earn, all of the above personas can apply.

With in-game economies, we witness a new persona emerge. I predict this persona will be rampant in play-to-earn games, as games lower the barrier between in-game money and cash.

The merchant, the robber baron… and keeping with the poker cards metaphor: the Dealer.

The dealer doesn’t play the game: they play the metagame.

They optimize around achieving the highest return possible.9

In healthy amounts, dealers regulate the economy. When taken to the extreme, dealers monopolize markets, hoard inventory to create artificial scarcity, etc. This can prevent other players from progressing and playing the game as intended.

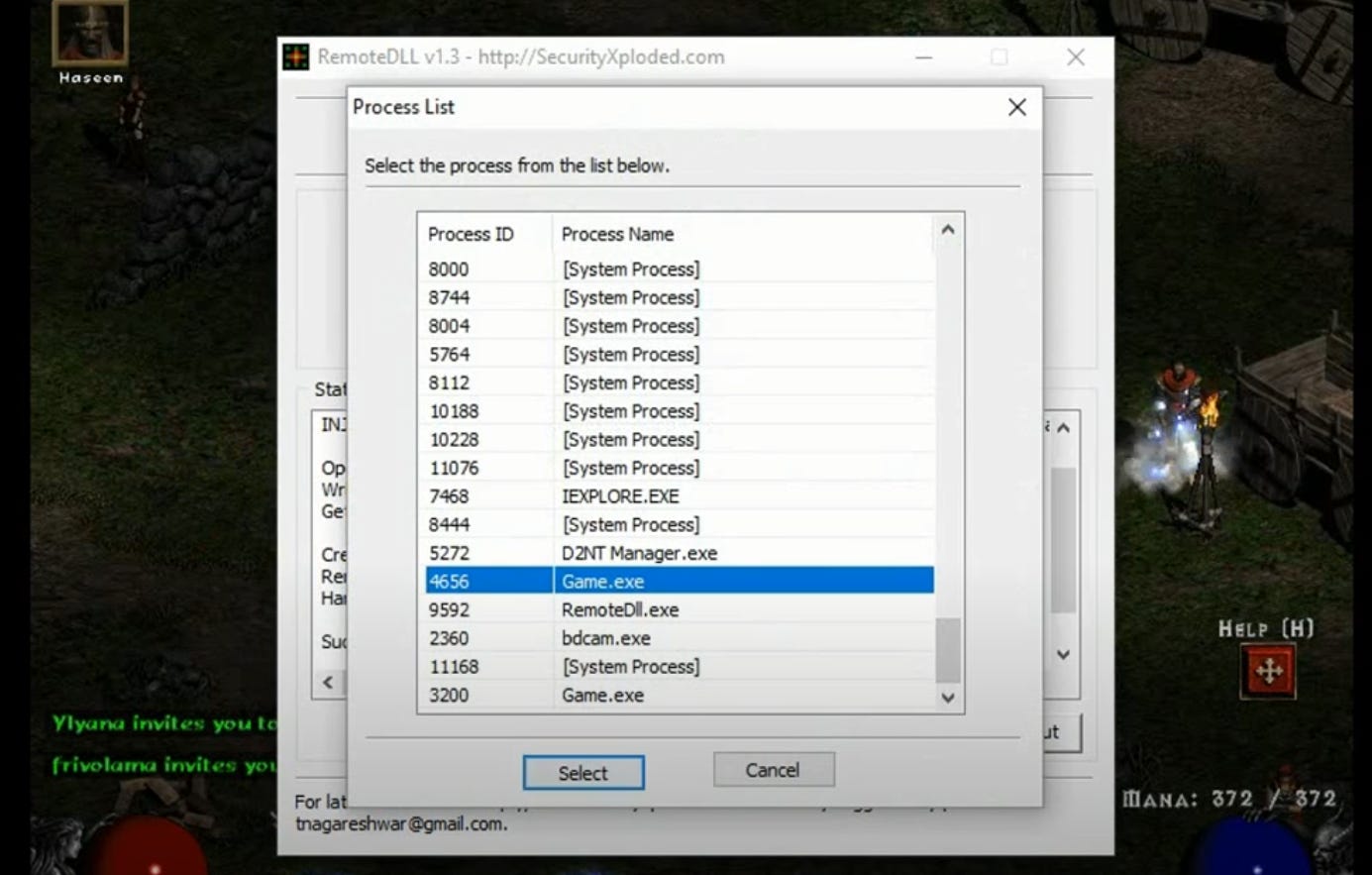

Examples of dealers: World of Warcraft Auction House players. People who run 50 bots in Diablo II and sells the proceeds on d2jsp10. Using bots to automate auctions on Neopets. (I have a friend who does this!)

We witness this type of player now in NFT marketplaces (flippers)11, and it won’t be difficult to transfer this mindset into videogames.

Managing the ratio of players who play to play, and players who play to earn is crucial. That comes with understanding the breakdown of players and their likely interactions with the in-game economy, and marketing a game to the right crowds, and with the right language.

But hey, for a future article :)

On a side note, I found an article I wrote back in 2018 on Diablo Immortal, nostalgia and monetization of IP. The ratio now stands at 32k likes - 770k dislikes.

———

I’m experimenting with a more punchy writing style for Metaversus. Let me know if this works via e-mail; you can reply directly when it hits your inbox.

If you liked the read, please subscribe, comment and share with a friend who’d enjoy this. Help elevate the discourse.

Or, you could just drop your favorite class in the comments (mine’s Paladin). :-)

Said by some philosopher, I guess.

I had an Hammerdin with Enigma, Shako and HotO. IYKYK.

We can compile that to our target language, English: “I would like to trade my Grand Matron Bow with the Faith Runeword, (Ohm Jah Lem Eld), for 2 High Runes”.

As for the one dollar bill, they used perfect gems, another in-game item.

This is really happening.

This involves buying more than they could use, trading and building relationships with others, forming communities and alliances. They’re ultimately mercenary.

A popular Diablo II items trading website. It functions as a gray market, and operates on a trust system: you send me the item, and I send you an intermediate online currency called forum gold. It has since extended to cover assets from Neopets and DotA 2.

Flippers buy something for low, and immediately resell it. They have literally no interest in the utility beyond how much money it can make them. They add utility by providing liquidity and price discovery functions, but also can cause volatility for the game economy.

Bringing to mind both pizza flipping, a popular metaverse meme (in Snow Crash, one of the premier real-world jobs is delivering pizza for Uncle Enzo), and Pudgy Penguins, a group of 8888 penguins sliding around on the Ethereum blockchain. The last one just sold for 0.8 ETH (2300 US dollars, at last count. Probably nothing.)

Ryan, amazing reading. I love the Dealer persona classification and the idea about managing them. Here you can find my opinion on how to fix current p2e state:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/play-earn-growing-trend-soon-forgotten-buzzword-michal-min%25C3%25A1rik